Opis

DEDICATION

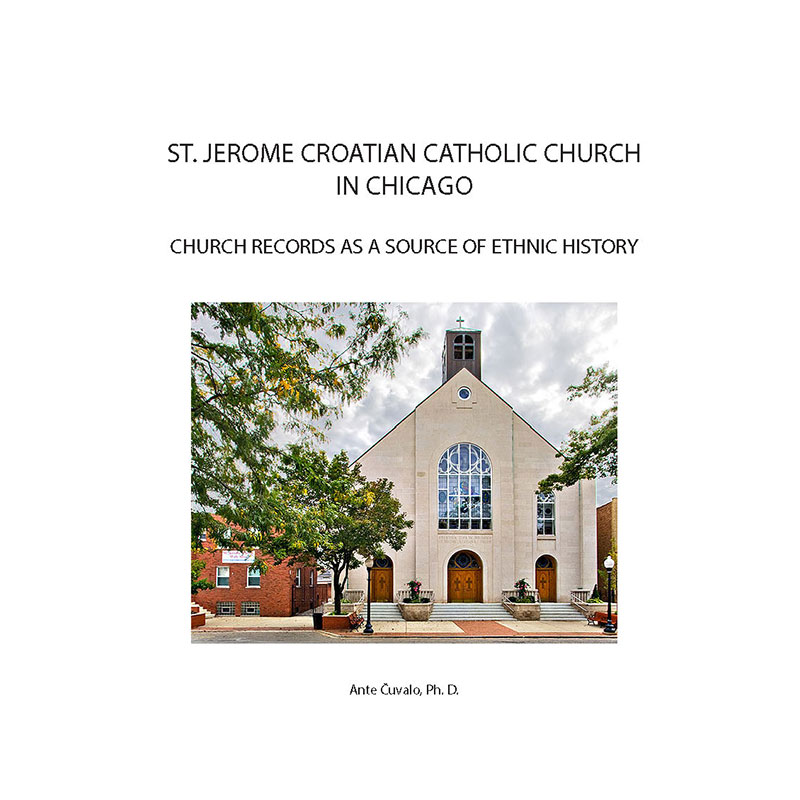

This book is dedicated to past and present parishioners of St. Jerome Croatian Church in Chicago on the occasion of the Centennial celebration of the parish.

Special thanks go to my daughter Andjelka Kulaš for the formatting and for help in transcribing names from the church registers, to my wife Ikica for proofreading the manuscript, and to Fr. Jozo Grbeš for his contribution.

CHURCH RECORDS AS A SOURCE OF ETHNIC HISTORY

St. Jerome CROATIAN CATHOLIC CHURCH IN CHICAGO A CASE STUDY

The following article was published in Review of Croatian History VII/2011, no. 1, Croatian Institute of History, Zagreb, Croatia

Catholic ethnic parishes in the United States have multiple functions, especially in the lives of newly arrived immigrants. In addition to fulfilling their religious needs, ethnic parishes provide many services, such as finding jobs, housing, getting a driver’s license, providing native language and folklore classes, and many other. They also serve as social centers and cultural repositories. At the same time, they play a great role as intermediary institutions. On the one hand, parishes help soften the harshness of life for those who find themselves in a new environment and, and on the other, they play a significant role in the process of Americanization, by introducing newcomers and their children to the American way of life.

Parish registers of baptisms, marriages, and deaths are a very valuable source of information and, when examined, provide much more than just names and numbers. They shed light on various patterns and processes, such as place of birth, birth rates, percent of inter-religious and inter-ethnic marriages, causes of death, life expectancy, integration into mainstream America, and other. This study focuses on St. Jerome Croatian parish in Chicago which is celebrating its centennial in April of 2012.

INTRODUCTION

Croatians in America

There are strong indicators that some Croatian seamen from Dubrovnik sailed with Columbus on his first voyage to what was later known as America, though this fact hasn’t been proven yet from any primary sources. It is certain, however, that already during the first decades of the 16th century Croatian sailors and captains, serving the Spanish crown or sailing under the banner of St. Vlaho/St. Blaze, came to the western shores of the Atlantic. From the early 16th century on, Croatians were coming to the New World in increasing numbers. Among the first arrivals there were some sailors (Mato and Dominik Konkeđević – c. 1520, Basilije Basiljević – 1537, and others), missionaries, and explorers (Ivan Ratkaj – 1680, Ferdinand Konšćak – 1730, and others), as well as adventurers who jumped off Spanish ships. Most probably, the name Croatan Indians in North Carolina is a living memorial to the 16th century shipwreck of a Ragusan (Dubrovnik) ship, whose survivors remained with the local natives leaving among them their posterity and Croatian name. An increasing number of Croatian immigrants began arriving to the United States during the first half of the 19th century. Most of them arrived through Central America, Mexico, and especially through the port of New Orleans. From that port they migrated northward to various places along the western coast. Thus, we already find a large Croatian settlement in San Francisco in the mid-19th century. Another major route of their migration from New Orleans, where Croatians had established a colony in the first half of the 19th century, was to the emerging industrial towns along the Mississippi river, primarily St. Louis and Chicago.

Croatians in the Chicago Metropolitan Area

Croatian presence in Chicago began in the mid-Nineteenth century. Historical research so far indicates that Joseph and George Randić were the first (or among the first) Croatians to settle in Chicago. In the 1870s, both appear listed as restaurant owners. In 1877, Joseph is also listed as a professional clerk (or perhaps there were two Joseph Randićs). These men (and maybe some others) must have been in Chicago before the 1871 Chicago fire, most probably in the early sixties. The Randićs came from the Bakar area, near the seaport of Rijeka.

The above mentioned individuals, and other early Croatian immigrants to Chicago, lived in the downtown area. A number of them became saloon keepers and restaurant owners. Sources from the 1920s tell us that about 15 such businesses were owned by Croatians before the economic crisis of 1893. They were located on Clark, State, and Wabash streets between Van Buren and Lake streets. It seems that those early comers became well-to-do individuals but they were not able (or interested) in organizing themselves as an ethnic community.

When the so-called “new immigrants” began arriving from Europe en masse toward the end of the 19th century, numerous Croatians were among them. Chicago, as a rapidly growing industrial and commercial center, was the final destination for many immigrants eager to find a job and improve their living conditions. It is believed that about thirty thousand Croatians settled in Chicago before the beginning of World War I. They settled in several city neighborhoods and adjacent industrial towns to the south and west of the city. Such settlements were located as follows: Wentworth Avenue and 22nd St., South Throop and 18th St., South Central Park, West Archer Avenue, Marshfield Avenue and 60th St., South Chicago, East Chicago, Ind., Whiting, Ind., Gary, Ind., Hawthorne (later incorporated into Cicero), Joliet, and smaller settlements in other towns to the south and west of the city.

Being that Croatians were (and are) mostly Catholic, the acquiring (or building) of local churches as their ethnic parishes, becomes a strong indicator not only of the neighborhoods where they lived, but also of the strength of their numbers in such neighborhoods, their organizational skills, and religious enthusiasm. Croatian Catholic parishes in the Chicago area were established in the following chronological order: 1900

– Assumption of BVM, Marshfield Ave.; 1903 – St. George (Croatian and Slovene, taken over by Slovenes a few years later), South Chicago; 1906 – Sts Peter and Paul, South Central Park Ave.; 1906 – Nativity of BVM, Joliet; 1910 – Sts Peter and Paul, Whiting, Ind.; 1912 – St. Jerome, Wentworth Ave.; 1912 – Holy Trinity (later renamed St. Joseph the Worker), Gary, Ind.; 1913 – Sacred Heart, South Chicago; 1914 – Holy Trinity, Throop St., 1916 – Holy Trinity, East Chicago, Ind., and 1973 – Guardian Angels-Bl. Cardinal Stepinac, N. Ridge Ave., Chicago.

St. Jerome Croatian Catholic Church – A Brief History

St. Jerome parish was established in 1912 by Fr. Leon Medić. A Protestant church building was purchased on 25th St. and it served the spiritual needs of the local Croatian community for 10 years. In 1922, another Protestant (Lutheran) church building was acquired and the parish moved to its present location on 28th St. and S. Princeton Ave.

Through its 100 years of history, the faithful were served by 21 pastors and 35 assistant pastors, all of them Croatian Franciscans. So far, the longest serving pastor was the late Fr. Ferdinand Skoko (1943-55 and 1956-58). The highly esteemed actual pastor, Fr. Jozo Grbeš, was first an assistant pastor (1996-2001) and then pastor from 2001 to the present.

The parish school was opened in 1922 and entrusted to the Sisters Adorers of the Blood of Christ, who educated the younger generations of Croatians and others for decades. The parish, its school, church hall, and other facilities, have had a significant impact on the life of the Croatian community in Chicago and local neighborhood as well.

Out of all the Croatian parishes in the Chicago metropolitan area, the community of St. Jerome has been the most vibrant. Besides its religious life and activities, it has greatly contributed to the preservation and promotion of Croatian cultural heritage in the city. All of this was achieved thanks to the efforts of hard-working and capable priests and very dedicated parishioners. In addition to that, the parish is located very close to downtown, and the neighborhood has been relatively stable through the years.

Church Registers as a Source of Ethnic History

The main purpose of this study is to examine St. Jerome’s parish registers (births, marriages, and deaths) from 1912 to 2002, which are a rich depository of information, and see how they reflect various patterns and processes in the parish community, from birth places of parishioners, their fertility patterns, assimilation, inter-religious and inter- ethnic marriages to life expectancy, causes of death, and places of burial. An attempt will be also made to see if and how these registers reflect the immigration patterns of Croatians to the Chicago area, as well as their social mobility, economic and working conditions. Furthermore, this research will contribute to the history of Croatians in America, as well as to the study of ethnic history in general.

Summary

During the first 90 years of its history, St. Jerome Croatian parish in Chicago had 6,207 baptisms, 2,092 marriages, and 3,615 burials. Out of the total number of baptized, there was approximately an equal number of males and females. Judging by the last names (although an imprecise criterion), about 18 percent of the baptized in the parish were of non-Croatian heritage, while the rest were of full or partial Croatian background. Most of the baptized, especially during the first two decades of the parish history, were the sons and daughters of those who came from the province of Dalmatia, more specifically from the area of Split and Sinj. The highest number of births took place in the 1920s, followed by a sharp drop-off in the 1930s, mainly due to the Great Depression. This change reflects the general pattern of birth rates in Chicago and in the country as a whole. There was a slight increase of births in the post-World War II period and also in the 1970s. A significant factor in the gain were two waves of new immigrants at the time. The parishioners of St. Jerome continued to follow long-held Croatian Catholic family traditions, which can be seen in the relatively small number of births out of wedlock, as well as civil and inter-religious marriages. However, the number of children per family is similar to the fertility patterns in Chicago, which is an indicator of the Americanization and modernization processes among Croatian immigrants in America.

The register of baptisms also provides valuable information on many of those who had been baptized at St. Jerome church but were married in other Catholic churches in the city and wider. The total number of such registered cases is 1,234. They were mostly second generation Croatian-Americans and some non-Croatians. Most of such marriages took place in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. Among the deciding factors to marry in an “American” church, it seems, was the desire to look beyond their ethnic parish community and integrate into mainstream America.

According to the parish marriage register, there were 2,092 marriages during the first nine decades of the parish history. The highest number of them took place in the 1920s. About 50 percent of marrying couples were of Croatian background. Out of that total, about 50 percent of bridegrooms and about 37 percent of brides were born in Croatia. Clearly, more Croatian born men than women were marrying American born spouses. Among the brides that came from other ethnic backgrounds the highest number of them were of Czech nationality, especially during the first decade of the parish history. Only about 8.6 percent of marriages at St. Jerome church were among individuals of different religions, out of which there were more non-Catholic husbands than wives. Most of the brides marrying at St. Jerome were in the mid-twenties and the grooms in the late-twenties. Although the registers do not provide the number of divorces, we do find that among those who were baptized at St. Jerome church and married elsewhere, 39 marriages were annulled by the Catholic marriage tribunal, while 24 were annulled among those who married at St. Jerome. The annulments began in the 1970s, after the Second Vatican Council.

During the first 90 years of the parish history, 3,615 deaths were registered in the church books. Out of that, over 60 percent were males and close to 35 percent females, and the rest were babies whose gender was not indicated. The highest number of deaths occurred during the 1920s. Besides the main causes of death in the early 20th century, which were infant deaths, pneumonia, and tuberculosis, there was a high number of deaths caused by work-related accidents, as well as violent deaths which indicates the working and socio-economic conditions in this ethnic neighborhood, as well as in the city of Chicago at the time. The greatest number of St. Jerome’s faithful departed were laid to their final rest at St. Mary Catholic Cemetery (2,203), followed by Mount Olivet Catholic Cemetery (981). While one might be astonished by the low average age of those who died in the 1920s, the register clearly indicates that there was a constant rise of life expectancy so that by the 1980s it had reached the age of low seventies.

The founding and history of St. Jerome Croatian Catholic church reflects the lasting religiosity and ethnic identity of Croatian immigrants in America. Although ethnic intensity diminishes over time, because of assimilation, social, economic, and geographic mobility, the church registers prove the persistent role of St. Jerome Church, and other ethnic parishes, in the religious and cultural life of Chicago and America.

Ante Čuvalo